How voting for your House of Representatives Member works

2022-04-27

Introduction

Australia uses preferential voting to elect candidates to the House of Representatives. Preferential voting is also known as instant-runoff voting or ranked-choice voting. In this article, we’ll break down how preferential voting works in detail, using the Division of Clark as an example.

This article remains entirely independent of political opinion. Two opinions are cast: one on voting systems, which we talk about next; and one on How to Vote Cards, which we talk about at the end.

Before making this article publicly available, I asked the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) to review it, and provide commentary on any inaccuracies so that they might be fixed. Although they haven’t officially approved the content, with their input, I am confident that it’s an accurate representation of our voting system. However, you should trust all communication by the AEC above what you read here.

In this post, we’ll talk about:

- How preferential voting works

- Case study: Division of Clark

- Who really does the preferencing?

How preferential voting works

When we want to tally what people want, it sounds intuitive to go with what most people want. There are many ways to do this. The simplest way is to have everyone vote once, and pick the group that has the most votes. This kind of voting isn’t very fair because it often leads to choosing a candidate that has the most votes at a glance, but really is in the minority. For example, let’s say there were ten people ordering three pizzas. If the meatlovers and supreme pizzas both got three votes each and the cheese pizza got four votes, it looks like cheese is the most popular; but in reality, there are six people who wanted something other than a cheese pizza, and so ordering a cheese pizza isn’t really fair to them. This is a bad system for working out which pizza to order, and a catastrophically bad one for choosing the people to govern your country.

Fortunately, Australia doesn’t use this kind of voting in our elections. Since the 1918 general election, we’ve used preferential voting for electing our Members to the Lower House, which means that we rank each candidate in the order we would want them to represent our interests in parliament. This means that even if the rest of the electorate doesn’t agree with us on our first choice, we continue to get a say in who represents us until someone is picked. In other words, provided you fill out your ballot paper according to the rules, it’s impossible for you to waste your vote.

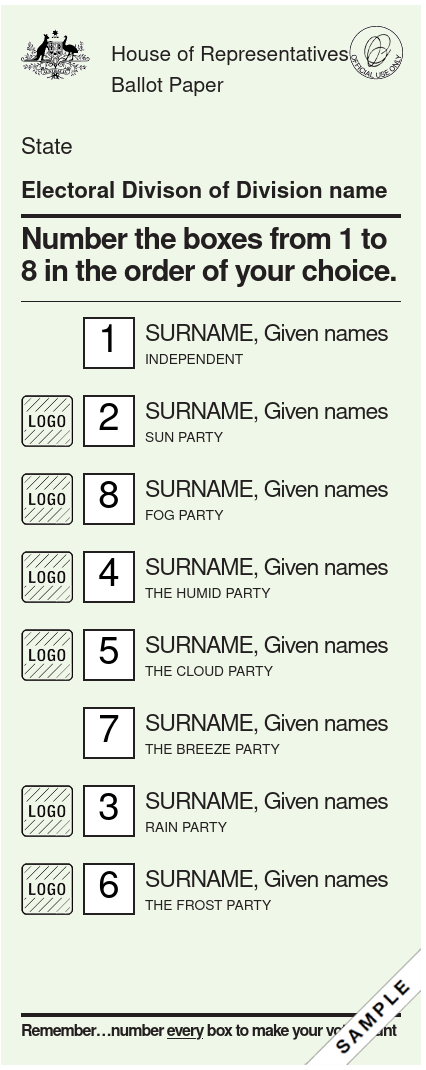

The rules are very simple: number all the boxes in the form of 1, 2, 3, and so on, until you’ve filled all the boxes with your preferences. Make sure that each box is clearly marked and easy to read. The AEC provides us with pencils instead of pens to make sure that our results don’t smudge when writing or counting. Don’t provide any identifying information (such as your name, address, date-of-birth, etc.). We call a ballot paper that’s followed all the rules a formal ballot. Only formal votes are counted and contribute to the election result. The AEC provides a lengthy guide outlining what constitutes formal and informal ballots and they also have a practice mode. Below is an example of a formal ballot paper from the practice mode.

Case study: Division of Clark

We’ll start this section by filling in our own ballot paper, then move on to how the votes are counted.

Filling in a ballot paper

For this article, we’ll use the AEC’s “example of distribution preferences” for the Division of Denison in the 2010 federal election. Following a redistribution, Denison was renamed to Clark in 2019.

| WILKIE, Andrew | |

| JACKSON, Jonathan | |

| BARNES, Mel | |

| SIMPKINS, Cameron John | |

| COUSER, Geoffrey Alan |

Let’s now fill in the boxes. The choices for the numbering are for demonstration purposes only, and don’t reflect my real voting preferences.

| 5 | WILKIE, Andrew |

| 3 | JACKSON, Jonathan |

| 1 | BARNES, Mel |

| 4 | SIMPKINS, Cameron John |

| 2 | COUSER, Geoffrey Alan |

Notice that all the boxes are filled in. This is required for your vote to be formal. If you leave more than one box blank, your vote won’t be counted. Also notice that each box has a unique number. This is also required for your vote to be formal: even if you like two candidates equally, you’re going to need to choose one over the other. Finally, notice that the numbers go from one to five. You need to use the numbers one through however many candidates there are for your ballot to be formal.

Counting the votes

Australian law only permits paper ballots. That means that no one is voting on a computer, and real humans are counting the votes. All polling stations have multiple officials at all times, so there’s no chance for someone to mess with your vote. Candidates are allowed to appoint representatives to ensure the integrity of the polling stations in their electorate remain intact. These representatives are called Scrutineers. Under Australian law, a candidate needs more than half the electorate’s votes in order to be declared the winner. If no one has that, then the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated, and votes for them are redistributed according to how you told the counters to move your vote. This process repeats as many times as necessary, until someone has more than half the votes.

When officials begin counting votes, they first organise the ballot papers into groups where all the candidates with a 1 next to their name are in the same group. That means in the Clark electorate for the 2010 election, there were five initial groups, with our sample ballot being in the BARNES group. The ballots are then checked multiple times to ensure their allocations are correct, after that, they’re counted.

| Accumulated votes | Candidate | Status | Our ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13788 | WILKIE, Andrew | 5 | |

| 23215 | JACKSON, Jonathan | Lead | 3 |

| 856 | BARNES, Mel | 1 | |

| 14688 | SIMPKINS, Cameron John | 4 | |

| 12312 | COUSER, Geoffrey Alan | 2 |

Once this round of counting is complete, we move on to the next step. The candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed according to the voters’ wishes. In our case study, that means Mel Barnes is eliminated. Because we said Mel Barnes was our first preference, that means the counters will look at our ballot, see who has the number two next to their name, and put our ballot in that group. In this case, it’s COUSER. The ballots are checked again for correctness, and then counted.

| Accumulated votes | Candidate | Status | Our ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13788 + 269 = 14057 | WILKIE, Andrew | 5 | |

| 23215 + 229 = 23444 | JACKSON, Jonathan | Lead | 3 |

| Excluded | |||

| 14688 + 98 = 14786 | SIMPKINS, Cameron John | 4 | |

| 12312 260 = 12572 | COUSER, Geoffrey Alan | 2 |

This process iterates until there’s a candidate with more than half the votes of the whole electorate. In the second round, COUSER is eliminated because that group has the least number of ballots. The people in the COUSER group are then redistributed according to the voters’ preferences. If someone voted one for COUSER, then their vote goes to their second preference. In our case, COUSER was already our second preference, so our ballot goes to our third preference: JACKSON. Again, the ballots are checked to make sure they found their correct homes, and then counted.

| Accumulated votes | Candidate | Status | Our ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13788 + 269 + 6635 = 20962 | WILKIE, Andrew | 5 | |

| 23215 + 229 + 4888 = 28332 | JACKSON, Jonathan | Lead | 3 |

| Excluded | |||

| 14688 + 98 + 1049 = 15835 | SIMPKINS, Cameron John | 4 | |

| Excluded |

SIMPKINS is the next candidate to have the fewest number of votes and be eliminated. Because this is round three, preferences two through four will be considered for allocation. Our ballot wasn’t in the SIMPKINS group, so it didn’t move. Unsurprisingly at this point, the ballots are checked, and then counted.

| Accumulated votes | Candidate | Status | Our ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13788 + 269 + 6635 + 12525 = 33217 | WILKIE, Andrew | Winner | 5 |

| 23215 + 229 + 4888 + 3310 = 31642 | JACKSON, Jonathan | 3 | |

| Excluded | |||

| SIMPKINS, Cameron John | Excluded | ||

| Excluded |

We’re now down to two candidates, and whichever group has the majority of votes will be declared the winner. In this case it’s WILKIE, so Andrew Wilkie became the representative for the Division of Clark. With preferential voting, we see that even though Jonathan Jackson had the most votes to start, they weren’t the candidate with the most votes in the end.

Who really does the preferencing?

Finally, there seems to be a lot of confusion about who preferences votes. People choose their preferences, not parties. Parties often hand out things called How-to-Vote cards, which are them telling you how they would like you to vote. This might lead you to believe there’s only a handful of ways to validly vote in an election. This isn’t true.

While there would have been a maximum of five different How-to-Vote cards in the Clark electorate for 2010, there were actually 120 different valid ways to fill out a ballot. When casting a ballot, it doesn’t matter what parties tell you on those cards: only you choose how you want the candidates to be preferenced.

When voting, you can refuse to take How-to-Vote cards from campaigners and if someone forces one into your hand, you can always throw it in the bin. Only you decide your vote.

Conclusion

In this article, we learnt how Australians elect Members to the Federal House of Representatives, how to fill out a formal ballot paper, how preferential voting works at a technical level, and that only you choose how you preference the candidates.

We’ll dive into electing Senators in the next article.